Photographed by Ankush Samant

Mobile Autonomy

The mobile phone’s exponential market growth has been driven by the increasingly ubiquitous “cheap cell phone,” which has made mobile technology accessible to workers and bosses alike, radically altering how work gets done, how people interact, how individual and communal relationships are organized, and indeed, how identities are shaped and projected.

It might seem superfluous to point out that in none of these cases was the mobile phone itself responsible for the wrongs committed. And yet, it is the device which becomes the object of regulation—on the logic that controlling access to the device keeps in check the undesirable behaviours or outcomes in question. We see this most clearly in the opposition to women using mobile phones, which is both regional and class-specific. Jeffery and Doron remark on the presence of “mobile wali” (literally, mobile woman) in Bhojpuri popular music: a seductive image of a jean-clad alcohol-consuming woman who dances freely while talking on her mobile phone. Tasveer Ghar, a digital archive of South Asian popular visual culture, places mobile wali alongside paan-wali (woman betel nut vendor) and bicycle-wali (woman riding a cycle): together, the new symbols of women’s emancipation and progressiveness. In my own conversations with cell phone users in the southern states, it has not been unusual to find conservative lower-to-middle and middle-class families regulating and even disallowing the cell phone use by grown daughters, and particularly daughters-in-law. Explanations range from the avowed absence of need—difficult to prove, difficult to deny—to less conscionable theories of how mobiles foster “rape culture.” Just this July 2014, Karnataka MLA Shakuntala Shetty, who chairs the Legislative House committee for Women and Child Development, blamed the device for rising rape and molestation cases—to considerable public outcry. The committee proposed a ban on mobile devices in schools and colleges on the grounds that “mobile phones are debasing the educational atmosphere in schools and colleges.” A community leader from Haryana, the rural state adjoining Delhi in which unelected all-male panchayats can exert considerable social influence, explained it thus to Ellen Barry of the New York Times: “The mobile plays a main role… You will be surprised how this happens. A girl sits on a bus, she calls a male friend, asks him to put money on her mobile. Is he going to put money on her mobile for free? No. He will meet her at a certain place, with five of his friends, and they will call it rape.”

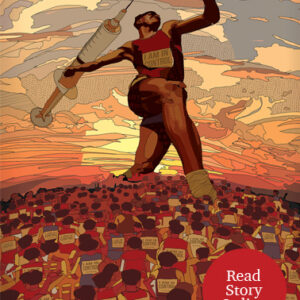

Such narratives can be perplexing, to say the least. Analysts often respond by explaining that the mobile phone challenges traditional sources of authority enough to generate profound anxieties. For example, Jeffrey and Doron cite Manuel Castells’ insight that “mobile communication is not about mobility but about autonomy.” The mobile phone unsettles old social structures by introducing new forms of autonomy, they conclude.

It is not difficult to appreciate the mobile phone’s transgressive capacities, or how it can enable the assertion of independence and agency against convention and hierarchy. The mobile phone is often celebrated for its equalizing, democratizing capacities, always centred on empowering individual users to break free of constricting traditions. Ironically, it is the mobile’s association with individual autonomy to which social conservatives object. They group it then with objects like jeans, or practices like consuming alcohol or holding “DJ parties” as quintessential signs of individual agency in a highly contested Indian modernity. Compelling though it may be therefore to pivot the mobile phone between “tradition” and “modernity,” “hierarchy” and “democracy,” communality and individualism, such explanations remain somewhat wanting. Neither do they address the ways in which the mobile phone meshes these binaries, recalling the modernity of tradition or the hierarchies within democracy, nor does flattening the mobile phone into a simple instrument of individuation quite capture the force or the power attributed to the device itself. End